I first met 2012

Nelson Algren Award winner

Jeremy T. Wilson while volunteering at 826CHI. I'd be up in front of a class of

twenty or so second graders trying to get them to focus long enough to

collaborate on an original story while Jeremy sat in the back reading and

presumably assisting Admiral Moody, 826CHI's unappeasable curmudgeon of a

publisher. Every now and then my walkie talkie would hiss to life, and

Admiral Moody would come on to threaten my job if I didn't get him a story

pronto, a call which would set the kids squeaking and bouncing with glee.

I never did figure out the exact nature of the relationship between

Jeremy and Admiral Moody, but Jeremy was the only person I ever knew who got to

go back there to see the reclusive man in the flesh.

Jeremy and I also volunteered for the small-group storytelling 826 does with the slightly older kids. The first time I heard

one of Jeremy's groups get up to read their story I was blown away by its

imaginative verve and humor. It simply towered above the other groups'

offerings. "He must have had a really good group," I told

myself. Then it happened again, and again, and again. I knew this

guy was a writer, and I had to get to know him.

Jeremy and I started getting together for beers about once a month, and

then I pitched the idea that we meet to write, each of us working on

our own stuff, for two or three timed periods of 45 minutes each. For two

years we sat down once or twice a week with our laptops open across the

table like we might be playing Battleship and banged furiously away at the

keys until the timer released us. From there we transitioned into writing a screenplay together.

You should know that it's going to be really good, and you should

consider making an offer now before we put it on Ebay and the bidding war

drives it out of reach.

Over that time, Jeremy has not only won the

prestigious Algren Award--a BFD in the non-sarcastic use of that

acronym (if there be such a thing)--he's also become a father, completed an MFA

at Northwestern, travelled to Prague on a fellowship to participate in a

writing workshop led by Stuart Dybek, and steadily published his short stories

in literary magazines, one of which got him nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Getting nominated for a Pushcart is about

the coolest thing that can happen to a short-story writer. If he wins,

I'll probably be unable to face him and will string myself up with a

suicide note pinned to my shirt that says, "I am happy to hear about your latest award."

Yes, I stole that image from Philip Roth (and I realize mine is not nearly as funny).

Here then is Part I of our rangy conversation about writing,

publishing, reading and lots of stuff you wouldn't think has anything to do

with any of that other stuff.

Logomancers:

A lot of writers are looking for that big breakthrough moment, that moment when

someone recognizes their work and all of a sudden it's like you're writing

downhill for the rest of your life, but once you've been publishing for awhile,

you start to realize it doesn't happen quite that way, right? I mean, you get a

little attention here and a little attention there and sometimes one thing

leads to another but sooner or later the dust settles, and it's just you and

the page and now what? How has it been writing in the aftermath of winning the

Algren Award?

JTW: Right

after everyone heard the news on Sunday my email and Facebook wall lit up with

congratulations and warm wishes and it felt so incredibly great to be

recognized and to have so many people want to read my story. As you know, we're

used to getting fired up when a rejection letter tells us we don't suck so

badly, so this felt like winning the lottery. But by Tuesday it was all over.

And it was just another Tuesday where I had to get the job done, which is the

theme of this answer.

In 1997 I published my first story in an anthology titled O' Georgia: A Collection of Georgia's Newest

and Most Promising Writers. Don't look for it. Trouble was I believed the

subtitle. I believed that not only was I new I was also promising. I didn't

publish another story until 2007. I was 23 when that first story got published

and I thought, like you said, that I'd be writing downhill for the rest of my

life. What happened instead was that my friends read the story and no one came

begging for more, which was good because I didn't have more unless they wanted

to read my journals. It was also good because at that point I had no idea what

I was doing even though I thought I did. Since the agents and publishers didn't

line up the driveway I had to go out and find a job. I guess I'm telling you

this story just to say that it took me a long time to realize that no matter

what recognition you receive there will always be a moment when the dust

settles, when it's just another Tuesday and it's "you and the page and now

what?" So if you can do this everyday, make it a habit, sit in front of

your computer or in front of your paper or typewriter or whatever and make

yourself get the job done, you start to get used to writing without anyone

paying attention. This is not easy. But don't you think that to write from a

place that feels most free you really have to convince yourself that nobody's

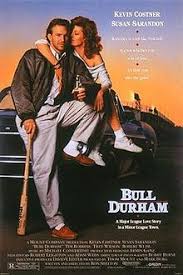

watching and you'll never have success again? It reminds me of Bull Durham. Crash Davis says of

baseball: "You've got to play this game with fear and arrogance." I

think that's true for writing as well. Look at me, I just compared baseball and

writing. No one has ever done that except for me and Marianne Moore. Nuke LaLoosh repeats Crash's words

back to him saying jokingly: "Fear and ignorance." I think that's also

true of writing.

Logomancers: I totally agree you have to write like

no one is watching or like you'll never have success again. In fact, I'd even

go so far as to say that you have to get rid of the thought that no one is

watching and that you'll never have success again because in so far as ANY

ideas about what you're doing arise while you're writing, you're asking for

trouble. I know whenever that happens to me, I lose track of what I'm writing

and then I look down on the page and there it is, a platitude or some sort of

soft shortcut I didn't feel at all and never meant to take because I've lost

the thread of the voice and the current of the inquiry. My mind has moved onto

other things, and it's obvious on the page. Do you ever feel like you see this

happening when you are reading someone else's story? I remember some writing

book I read one time suggested that when your mind wanders while reading, it

may not be you, it may be that the writer's mind was wandering while he or she

was writing. It's probably not always true, but that idea has stuck with me,

and sometimes I feel like the whole discipline of writing is nothing more than

a repeated effort to bring all of my attention to the work so that I'm

listening, seeing, and pushing forward with a sort of intense inquisitiveness.

It reminds me of a quote by William James, "The

faculty of voluntarily bringing back a wandering attention, over and over

again, is the very root of judgment, character, and will." Maybe we could

also add "good writing" to that list. I like what you said about

needing both fear and arrogance AND fear and ignorance (because who would ever

think being a writer is a good idea?). Do you think we should also add fear and

loathing? How do you approach your discipline when the work turns on you and

you start to hate it and yourself for not only making something so terrible but

for ever deluding yourself into thinking it might be worth someone else's

$12.95?

JTW: I'll work backwards on this one. I guess I rarely get to the

point where I hate something I'm working on that much because if I hate it to

the point of self-loathing I'll just stop and write something else or go for a

run or read someone's work that inspires me and makes me feel like I can

continue doing the ultimately silly thing that is writing stories. But I do get

to the point where the story stops on me and for one reason or another I just

can't keep going. At that point I put the work away or send it to a trusted

friend/reader or send it to a trusted friend/reader and then put it away.

Sometimes I come back to it sometimes I don't. I don't know if this really

answers the question or if I'm even really being honest here now that I think

about it, of course I hate what I'm writing sometimes! But it just makes me

want to try to wrestle with it until one of us gives in. The key is not to give

in too easily. This can be difficult.

For the most part books are still pretty cheap dates considering

all the cool shit you can get into in a book. I'm not trying to say that a

short story or novel can save the world or anything, but it can help strengthen

the imagination or help a person feel the slightest bit of empathy or

excitement for a character or culture or experience that is new or foreign or

alien, and maybe that does turn out to change a little morsel of something in a

person's soul. That's worth $12.95. Actually, it's so valuable it should really

be free. So support your local library. I see your William James and raise you

some Joseph Conrad: "Only in men's imagination does every truth find an

effective and undeniable existence. Imagination, not invention, is the supreme

master of art as of life." Is it possible to read without using your

imagination?

My mind wanders all the time when I'm reading and writing. I'm

glad to hear that I can now blame the author instead of the fact that the Braves

are on my TV. I have this experience you're talking about far more frequently

in a novel than I do in short stories, which sounds obvious. Somewhere in the

middle of most novels I read I feel like I could stop. I'm bored. I don't care

anymore. Nothing new is happening. Pages and pages of beautiful prose are

killing the plot slowly and elegantly. Maybe me saying all this proves I'm a

novice. Maybe it means I'm a short story writer. I read recently someone saying

that certain writers are one or the other, a novelist or a short story writer,

and that some writers can do both, but they are always better at one than the

other. Is this true? Probably not. Richard Ford has written like a bad ass in

both forms. There are others. Give me some others.

"Writing is nothing more than a repeated effort to bring all

of my attention to the work so that I'm listening, seeing, and pushing forward

with a sort of intense inquisitiveness." This is really good, and I wish

I'd said it. You sound like a writer.

Logomancers:

I wish I could take all the credit for that. I think I got at least half of

that from Madame

Zabaletsky. It sounds to me like you have a pretty healthy strategy for

dealing with frustration and getting stuck. Was that something you had to

learn? I mean, you may not have erred on the side of banging your head against

the keyboard like me and Don Music, but did you

err on the side of walking away from a particular piece and never coming back?

I agree that books are an excellent value, but sometimes I'm awed

by the fact that there are so many of them out there, and I imagine my words

going into a giant pile of all the words that have ever been written, and I

think, "Who could get any use out of that heap and why would I ever add to

it?" I know what you mean, though. Stories help us exercise and strengthen

our imaginations, and I do believe that the imagination can open us to an

ever-widening, more inclusive perspective. That's definitely worth $12.95 or a

trip to the library, and what you said earlier about success probably holds for

value, too. If you worry about the value of what you're writing while you're

writing, you're dead, and it's not like you can stop writing, so why worry?

I don't want to make too much out of who's responsible for the

wandering attention thing. I feel like reading is a collaborative act between

the reader and the writer to co-create an imaginal experience. I want to say

you need both attention and imagination to read or write, but I also feel there

is a distinction here that deserves to be aired. I'm thinking here of something

Richard Hugo says in his essay, In Defense of

Creative-Writing Classes. Hugo writes:

"From experience and observation, I've come to believe

reading has as serious a relation to writing as do any number of activities

such as staring pensively out the window or driving to Laramie. A very serious

relation at times. At other times no relation at all. The writing of a poem or

story is a creative act, and by 'creative' I mean it contains and feeds off its

own impulse. It is difficult and speculative to relate that impulse to any one

thing other than itself. Please understand, I'm speaking of the impulse to

write and not the finished work."

"From experience and observation, I've come to believe

reading has as serious a relation to writing as do any number of activities

such as staring pensively out the window or driving to Laramie. A very serious

relation at times. At other times no relation at all. The writing of a poem or

story is a creative act, and by 'creative' I mean it contains and feeds off its

own impulse. It is difficult and speculative to relate that impulse to any one

thing other than itself. Please understand, I'm speaking of the impulse to

write and not the finished work."

I included this mostly because it supports my suspicion that the

lethargy you feel when reading a novel has no bearing on your expertise as a

writer or whether you're best suited to write in one form of another. I can

think of lots of writers who have killed it in both forms: Hemingway, Faulkner,

Nabakov, Graham Greene, Conrad, Henry James, Joyce Carol Oates, Salinger,

Delillo, J. Joyce, Marquez, Wharton, Cheever, Bradbury (rest in peace), Capote,

Calvino, Tobias Wolff, Baldwin, Gardner, Updike and that's just from looking up

at the books on my shelf. I suspect writers probably tend towards one form over

another, but who knows what the future will bring? Do you feel any pressure to

write a novel? Do you feel like that's something you want or have to do

someday?

JTW: I think

you made the point that is to be made about this when you said writers probably

tend toward one form or the other, and just because we primarily write short

stories doesn't mean we always will, unless we're Alice Munro. But yeah, I

think there's always some kind of pressure to write a novel. Novels are serious

business and if you want to be taken seriously you have to write one. Not to

mention the fact that nobody reads short stories and only a fraction more than

nobody read novels. I don't really believe that but that's what I hear. I do

want to write a novel and hope that I can and will.

For me, reading has much more of a relationship to my writing than

would a trip to Laramie. If I'm not reading I'm not writing and if I'm not

writing I'm not reading. I've heard people say they can't read other writers’

work when they're writing. If that's true, then when are these people reading?

Either they're not writing enough or not reading enough or are so gifted they

don't have to read. That's not me. When I'm not reading I can feel my impulse

to write fading. The opposite is also true. The more I read the more I write.

As far as the influence a specific book I'm reading has on my written work at

the time, I see Hugo's point, a lot or a little, but the act of reading is

inextricably linked to the act of writing.

"Who could get any use out of that heap and why would I ever

add to it?"

Well, you, my dear friend, that's who. And because you've gotten

use out of it is as good a reason to add to the heap as any. This line of

thinking is an express train to Nihilist Town. I don't want to curl up into a

ball on my couch and lament the universe's vanity, so I guess I'll write a

story. I never considered myself the optimist in our relationship.

I have lots of pieces I've written and never come back to, don't

you? This is a byproduct of making writing a habit. It's impossible that every

day you'll sit down and start a line of creative inquiry worth pursuing.

Sometimes it's a dead end. But when you don't make a habit of writing it

becomes more and more difficult to recognize those dead ends and to let them

go. "But I've spent three months on this story, I can't just stop working

on it!" Sure you can, it sucks, move on. A lot of times these false starts

will find themselves into other stories or will resurrect themselves in a

different form, so, really, my use of the phrase "dead end" is

inaccurate. There are no dead ends.

Had Jeremy considered this conversation when he said there are no

dead ends? Will Jeremy and David ever resolve their artistic differences?

Does anyone, including them, care?

Tune in next time for Part II of

L&L's ongoing conversation with Jeremy T. Wilson.